I wrote about the OECD’s annual standardized test earlier this week, the PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), and today I am going to write about it again. Repetition is the key to these standardized tests, you know. In this particular post, I’d like to take a look at a few of the more subtle details from the report released by the OECD together with the results.

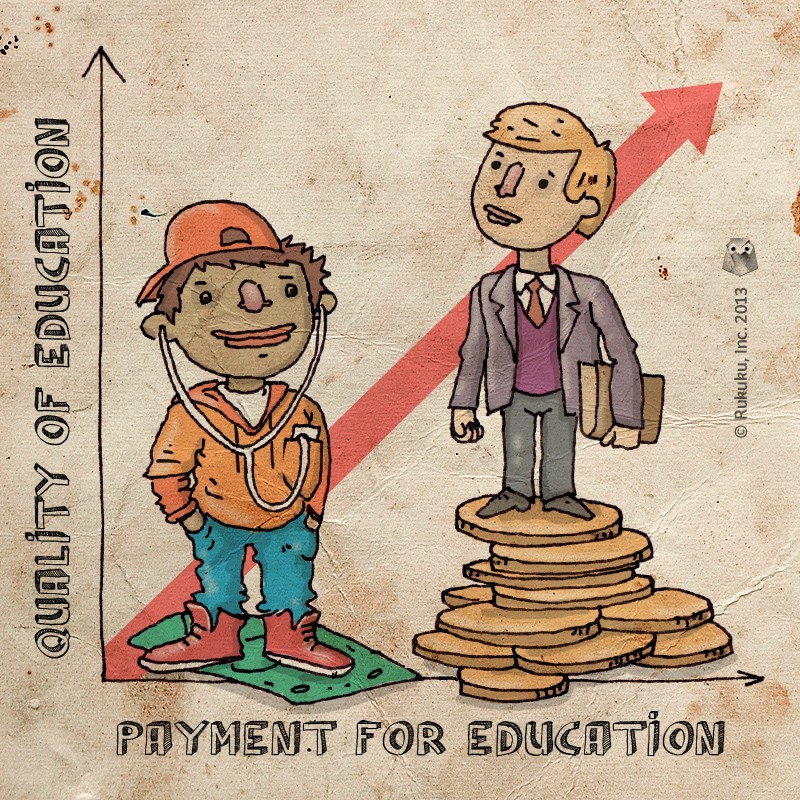

The first of those details is a big one because it relates to money. According to the OECD’s report, socioeconomic differences account for a 15% variance in the testing outcomes in the US, compared to less than 10% in Finland, Norway, Japan, and Hong Kong. In other words, two students from different socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to perform differently on the PISA in the US than in most other OECD countries. And it is not the student on the lower end of the financial spectrum that performs best.

Also, the OECD has a special classification for super rad students that are among the lowest 25% socio-economically but still perform in the top 5% academically. They are called “resilient.” In the US, only 5% of low income students classify as resilient, compared to 7% on average and around 15% for Hong Kong, Macao, Shanghai, and Vietnam.

This seems like it should be a strong point for the US. American dream, social mobility, all that, but as it turns out, it is the opposite. Ironically, unlike many other countries, the US does not show a big difference in the student-teacher ratio or teacher education levels in lower performing schools. So what is that difference? Facilities maybe? After school programs? I’d be very interested to hear any ideas in that big comment box below.

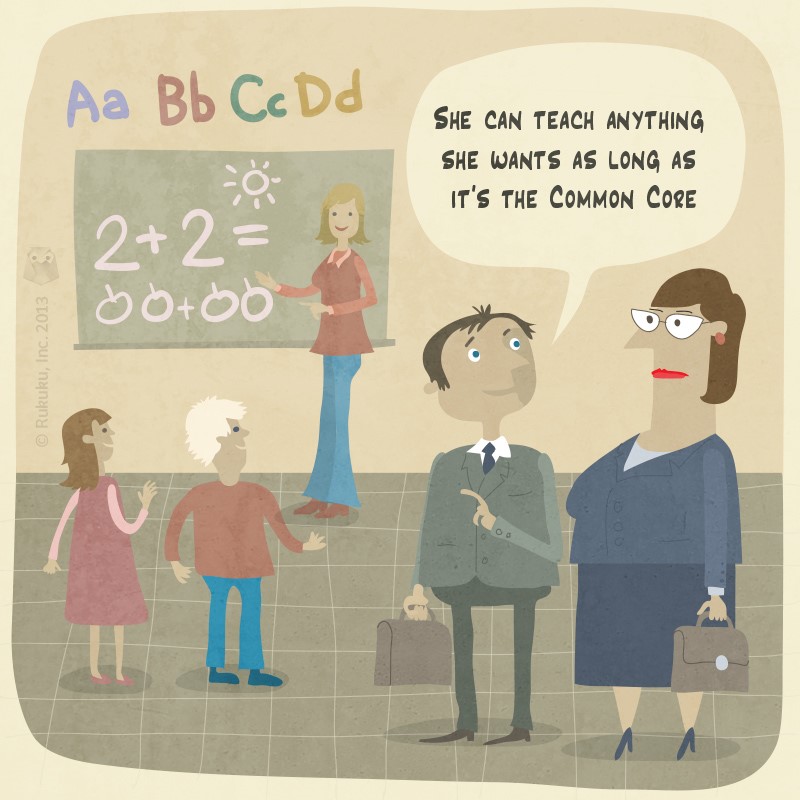

In terms of school performance, some interesting results came up as well. First, across all the OECD countries, schools with more autonomy tended to perform better. So, the more control the principal had, when combined with accountability measures and strong principal-teacher interaction, the better the students did.

At the same time, there was no cross-country evidence that competition among schools in any way contributed to better student performance. In other words, students at schools that compete to enroll more kids performed at the same level as students that are pretty much stuck with their schools.

On the positive side, or not really, the US did score well in opinions about our own math skills. This comes despite a below average ranking in math. For example, 69% of respondents felt confident in their ability to calculate figures such as the gas consumption rate of a car. The OECD average was 56%. So, at least we are confident. And have warning lights for low fuel.