Should computers grade essays?

The Common Core is trying to shift the emphasis of education toward more complex forms of thinking. Evaluating more complex thinking, however, requires more complex forms of assessment. I think most people would agree that written essays are better indicators of a students’ understanding than multiple choice, fill-in-the-bubble tests, but they are also more time-consuming and expensive to mark. Multiple choice tests can be fed into a computer and instantly graded, whereas essays require a teacher or professor or test center professional to read and evaluate them. Or maybe they don’t.

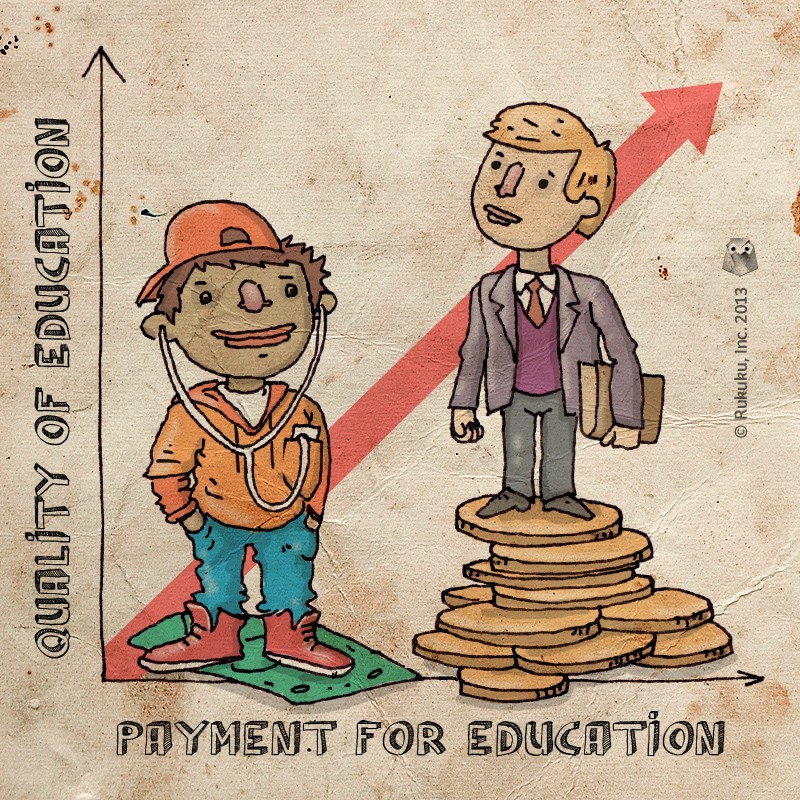

Several studies in recent years, like this one for example, have shown that computers can mark essays with the same accuracy and consistency as humans. In fact, computers are often more consistent than human readers. As states struggle to put together new assessments, without breaking budgets, computerized essay grading holds some obvious attraction. Namely, it’s much cheaper.

But it is also controversial and it’s not hard to imagine why. Computers can’t really measure creativity or originality. And the values placed on certain features, like longer words and more complex phrases, open possibilities for manipulating the scoring system. To see more on this argument, check out this statement from the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE).

What do you think, dear readers? Do you see any problems with computers grading essays? Leave comments below!