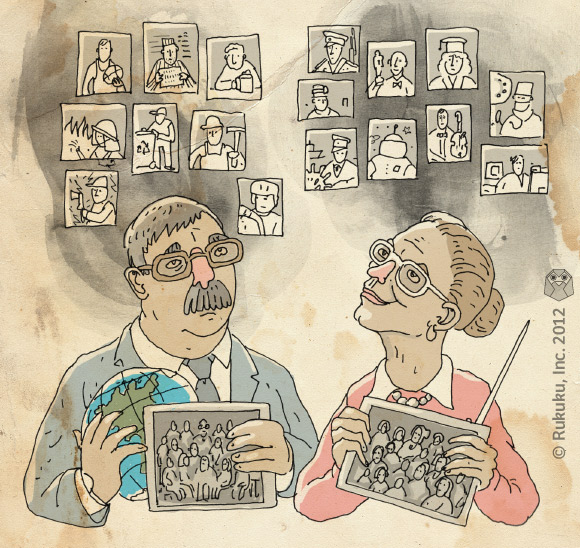

On this blog, we’re always talking about problems in education that need solving. One of these is the socioeconomic gap in access, quality, and achievement. What specific issues should stakeholders in education be aware of in solving this problem? Here are some examples:

High cost

Sure, in most countries public education is funded by the taxpayer, so it’s ostensibly free. Unfortunately, this isn’t the whole picture. Even in the developed world, public education is often of low quality, requiring learners to supplement their instruction with expensive, resource-heavy private services. And outside of primary school education, the world is full of people who want to learn something but aren’t able to because of prohibitive costs.

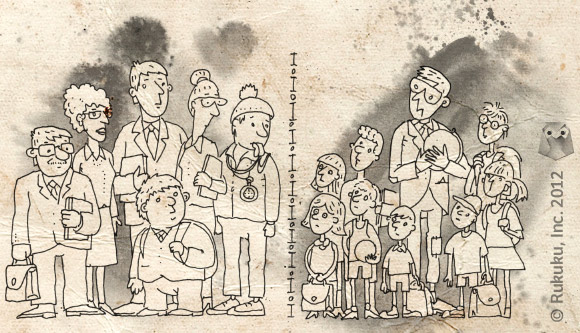

Poor access/low quality

In low-income areas of developed countries, as well as those in the developing world, access to quality education is in short supply. Good teachers are few and far between, and other educational resources are even more scarce.

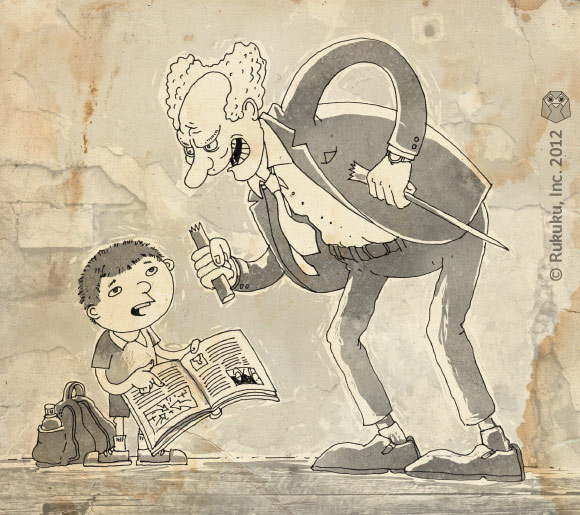

Lack of relevance

As we discussed in our commentary on curricular problems and in our last post, the things that are being taught in public schools are often irrelevant to the learners. For example, often people who require instruction in a trade will receive an abstract education that is of little use in advancing their career aspirations. There are no services broadly available to effectively and cheaply educate interested people in a subject they find relevant or necessary to their life or career advancement.

In our next installment, we’ll be talking about the ways in which online education technologies can help to address these issues.