Government policymakers everywhere want to make their schools better. To do that, many of them look to the country of Finland for guidance. That’s right, Finland. Finland’s education system places first in the world in several different rankings, including this one, conducted by Education firm Pearson. For comparison, Japan is fourth, Germany 15th, and the US 17th. After learning about the country’s stellar ranking, I wanted to know more. I did a bit of research (aka Googled Finland, Education), and learned some interesting facts.

First, and my favorite, Finnish elementary students have more fun. Elementary students in Finland spend around 75 minutes a day for recess, compared to 27 minutes for students in the US. Teachers get more free time, too, spending only four hours per day in the classroom, on average. That leaves more time for evaluation, reflection, collaboration, and further training,

Second, people really want to be teachers. In 2010, 6600 people applied for 660 teaching positions in Finland, according to sources cited by the Smithsonian Magazine. The reason is probably not the salary. Primary school teachers in Finland have an average starting salary of less than $31,000 and maximum salary of about $40,000, compared to $38,000 and $53,000 respectively in the US. The profession is highly respected, though, and the government pays for the masters’ degrees for those accepted into the education training program. All teachers must have master’s degrees.

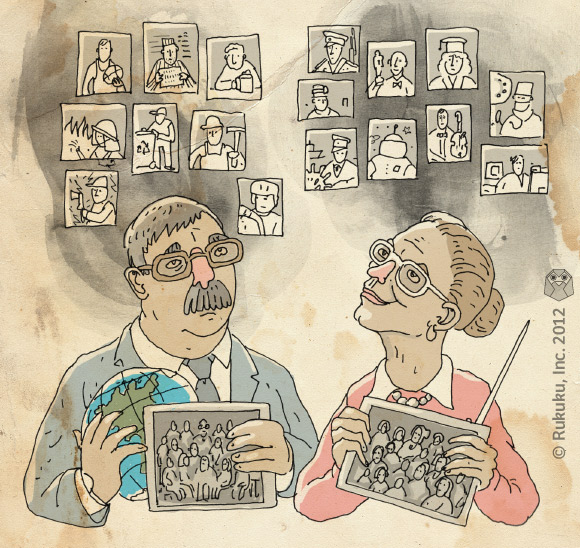

Those master’s degrees come in handy because the central government also gives a lot of autonomy to the country’s teachers and principals. The national government only offers broad guidelines, leaving it up to local officials and educators to determine the best methods for achieving those goals.

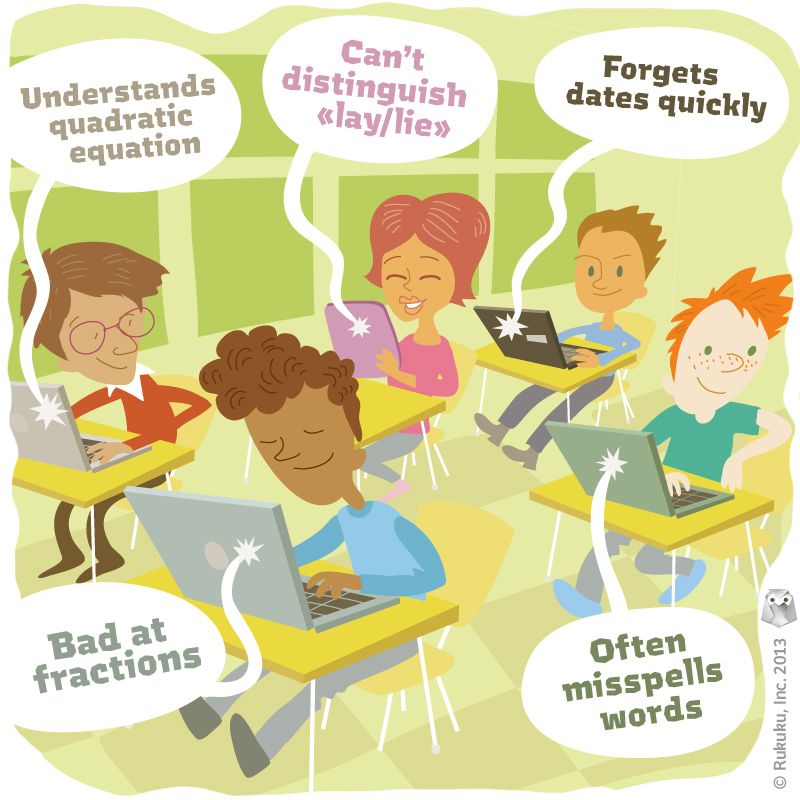

Finally, students usually have only one standardized test, which takes place when students are already approaching the end of high school. Students generally are kept in the same class as well, rather than separated into groups based on performance. As a result, the difference between the highest and lowest performing students is the lowest in the world.

There are many reasons why Finland’s educational model doesn’t translate easily to other places. The country is small, only 5.4 million people, and homogenous, with more than 90% of the population of Finnish descent. But even when compared to similar Scandinavian countries, or states like Kentucky or Minnesota, with similar demographics, its educational system outperforms.

So, which of these points – more recess for children, stricter requirements and more financial support and planning time for teachers, greater autonomy at the local level, or fewer standardized tests – do you think could be most beneficial for the educational system of your city, state, country?